Back from the Brink: Trumpeter Swans make remarkable recovery

/Story and photos by Robert Ferguson

This is a story about great loss and a subsequent remarkable recovery. It is a story of hardship and perseverance, tragedy and triumph. It is a factual account of how dedicated conservationists, led by one distinguished man, brought one of our most magnificent birds – the Trumpeter Swan – back from the brink of almost certain extinction.

The Trumpeter Swan is the world’s largest species of waterfowl, with a wingspan measuring seven to eight feet. Mature birds weigh as much as 30 pounds or more. In former times, Trumpeter Swans inhabited a broad expanse of North America. In Ontario, swans nested from the Great Lakes marshlands to the muskeg habitats of the Hudson Bay and James Bay lowlands. If you have ever heard the loud, resonating calls of a ‘Trumpeter’, then you can appreciate how its name was chosen.

With a wingspan approaching two-and-a-half meters, Trumpeter Swans are the largest of the world’s swans. Takeoff by a full-grown swan weighing up to 30 pounds takes practice and strenuous effort.

Biologists estimate that, prior to European settlement, the Canadian population of Trumpeter Swans east of the Rocky Mountains contained at least 100,000 birds. By the end of the 19th century, however, the population had been reduced to near zero. For almost a full century, the skies above Ontario’s wetlands remained silent. Not a single Trumpeter Swan was heard.

Prior to European settlement, Hastings County was sparsely populated, as was most of Ontario. Historians estimate that, in 1806, the human population of all of Upper Canada was about 71,000. Upper Canada stretched from the Ottawa River in the east, south to the shores of lakes Erie and Ontario, west to Lake Huron and Georgian Bay, and as far north as lakes Superior and Nipigon. By 1840, the population of Ontario had risen to 432,000. Just two decades later, the 1861 census counted almost 1.4 million! By the end of the 19th century, Ontarians numbered 2.2 million.

During the early days of the 19th century, wildlife populations and the landscapes that supported them existed as they had since the last great ice age. Cougar and wolverine still roamed the forests of southern Ontario in relative abundance. Migrating flocks of shorebirds, numbering in the hundreds of thousands, passed through the Great Lakes in spring and again in fall. Hunting parties described spectacular migrations of waterfowl that “darkened the skies” from horizon to horizon. But life was about to change.

An unintended consequence of such rapid human settlement was that wildlife populations began to decline. Pioneering families were large – 10 or 12 children were not uncommon – so parents had many mouths to feed. Several years of back-breaking labour were needed to transform 100 acres of maple and oak into productive fields of oats and barley, clover and alfalfa. Accordingly, farms in the early years following settlement were rudimentary and could not produce enough food to feed a family. Instead, families relied heavily on the bounty of wild flora and fauna to supplement their limited farm production and to see them through from one season to the next.

Waterfowl – ducks, geese and swans – were high on the list of favoured game birds because they were large, “meaty”, and relatively easy to hunt. We will never know to what extent our pioneering forefathers contributed to the decline in Trumpeter Swan numbers, because the levels of subsistence hunting were not documented. But we can speculate that the local impacts were likely substantial, especially by the mid-1800s when Ontario’s human population was surging past the one-million mark.

In the 1800s, there were no laws governing the hunting of migratory birds, so a family or hunting party could take as many birds as they desired. It wasn’t until 1916 when the governments of Canada and the United States implemented regulations regarding open and closed seasons, bag limits, and other measures to prevent indiscriminate killing of migratory birds.

Daily preening maintains a water repellent layer of feathers, which insulates the swans from frigid waters and sub-zero temperatures.

Trumpeter Swans were also targeted commercially for their gleaming white feathers. It is generally well known that the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Fur Trade played an important economic role in Canada’s early development as an embryonic nation in the 18th and 19th centuries. Less well known are the facts surrounding the trade in swan skins, the “Swan Trade”, which occurred during the same period.

From 1670 to 1870, the Hudson’s Bay Company held exclusive trapping and trading rights on all lands (“Rupert’s Land”) within the entire Hudson Bay drainage. According to Company records, 108,000 swan skins (most of which were Trumpeter Swans) were sold to the overseas London market between 1823 and 1877. Throughout Europe, as well as in cities like New York and Boston, the swans’ pure white feathers were in great demand for the fashioning of ladies’ hats and for making powder puffs.

Mute Swans, native to Eurasia, are increasingly common in southern Hastings County. They are easily distinguished from Trumpeters by their orange-red bills.

Swans were also killed for the stiff, flight feathers from their wings, which were used as quill writing pens. Historical records from the Hudson’s Bay Company show that in 1834 – in a single year – over 18 million swan and goose quills were sold overseas in the London market. Swans were even prized for their soft leather, which was used to make ladies’ purses.

The killing of swans, egrets, cranes and other migratory birds in North America and elsewhere became known as the “Plume Boom”. Those who opposed the slaughter of migratory birds for the sake of satisfying a fickle fashion industry named it the “Murderous Millinery”. Vocal opponents of the murderous millinery were instrumental in the eventual formation of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in Britain, and the National Audubon Society in the United States.

Ontario’s Trumpeter Swans were also exploited by market hunters along the shores of the Great Lakes, as well as in the United States where many of the migratory swans over-wintered. As the trickle of immigrants to North America in the 18th century became a flood in the 19th century, the need for food became greater and greater. The hunting of migratory birds then became a commercial venture. Market hunters killed countless waterfowl, shorebirds and other wildlife for profit, selling their bounty to fulfill the increasing demand for meat. Each fall, the migrating flocks of waterfowl entering the United States from Canada seemed limitless, and in the 19th century formed the basis for a thriving waterfowl hunting industry.

Sadly, the combined pressures from rapid human settlement, subsistence and market hunting, and the trade in swan skins were far more than the Trumpeter Swans could withstand. In the whole of Canada east of the Rocky Mountains, the population had been reduced from an estimated 100,000-130,000 birds historically, to almost zero by the early 1900s. The last wild Trumpeter reported in Ontario was in 1886.

The only remaining wild Trumpeters in North America were in remote and mountainous locations in Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Alaska, and in Yellowstone National Park (although the swans there were not discovered until 1919). In 1912, the plight of the Trumpeter Swan prompted Edward Forbush, a noted ornithologist and naturalist, to write, “The Trumpeter has succumbed to incessant persecution in all parts of its range, and its total extinction is now only a matter of years… The large size of this bird and its conspicuousness have served, as in the case of the Whooping Crane, to make it a shining mark [target], and the trumpetings that were once heard over the breadth of a great continent…will soon be heard no more.”

But in 1982, biologists and conservationists in Canada and the United States developed a comprehensive plan to restore Trumpeter Swan populations to self-sustaining levels. Swan reintroductions in South Dakota and Minnesota in the 1960s had shown promise, so there was optimism that recovery programs in other states and provinces would be successful.

The Ontario recovery project was led by Harry Lumsden, a biologist and research scientist with the Ministry of Natural Resources. In 1982, he set in motion an ambitious plan to restore wild populations of the Trumpeter Swan to Ontario. Young swans (hatched from eggs removed from nests in western Canada) were raised in captivity and were then released into suitable wetland habitats. The first release site of captive-reared swans in Ontario was at Wye Marsh, southeast of Midland, in Simcoe County. Between 1982 and 2006, when the restoration project ended, more than 500 swans had been released at 50 wetland sites in southern Ontario.

Lynn Gapes of Marmora offers corn to a growing flock of eager swans. The Trumpeter Swans of Hastings County are indeed wild birds, yet they seem to regard Lynn as “one of their own.” To a swan enthusiast, there is no greater compliment.

By 2008, the breeding population of wild swans in Ontario had surpassed the 1,000 mark, the minimum population goal set in 1982. Reaching this goal led waterfowl biologists to declare that Ontario had a “successful, self-sustaining population of Trumpeter Swans.” The Ontario population continues to grow in numbers and is quickly approaching the 2,000 mark. A formal, continent-wide survey in 2010 counted more than 46,000 Trumpeters in North America. What a remarkable recovery for a species that was once on the brink of extinction.

For his leadership and unwavering dedication to Trumpeter Swan conservation, Lumsden was awarded membership to the Order of Canada in 2004, our country’s highest honour for lifetime achievement. The Ontario Field Ornithologists honored him with their Distinguished Ornithologist Award in 2008. In 2012, Lumsden received the Lieutenant Governor’s Ontario Heritage Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Trumpeter Swans most often mate for life and pairs remain together throughout the year

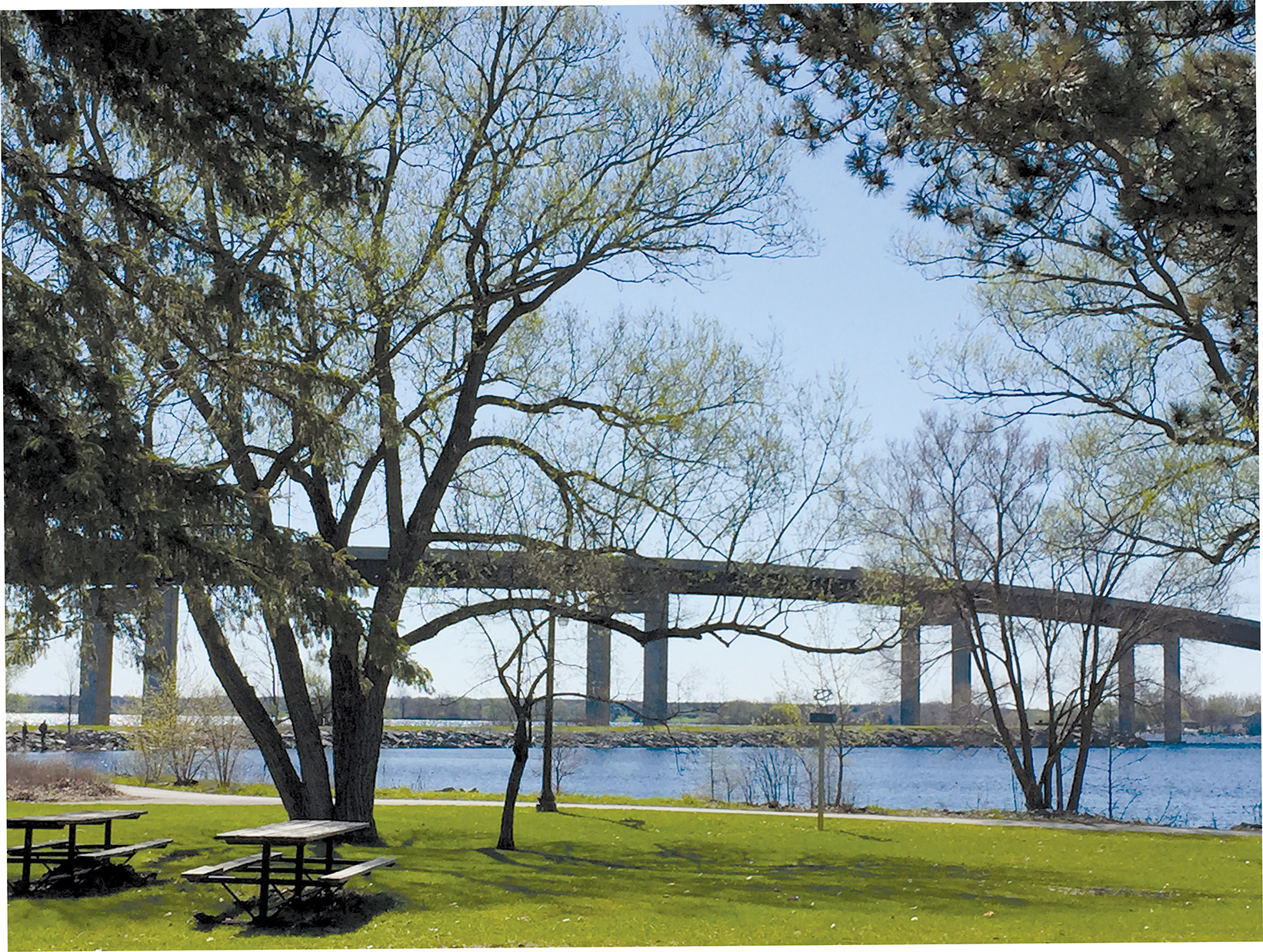

In Hastings County, the November–March period is the best time for viewing Trumpeters. During this time, they gather at ice-free areas along Lake Ontario’s shoreline marshes, as well as on the Trent and Crowe rivers where open water persists. Upwards of 30 swans can be seen at favoured feeding sites where river currents maintain open water, a critical component of over-wintering habitat.

Now – more than ever – we need champions of wildlife conservation like Lumsden. In today’s technological age of gadgets and gimmickry, our increasingly urban society is losing its connection with nature and with the other living things that share our world. As the global, human population surges towards the eight-billion mark, the challenges facing wildlife conservation have never been greater. With each passing year, governments around the world add more and more species to the lists of wildlife threatened with extinction. At times, the challenges ahead to reverse wildlife declines seem insurmountable. But Lumsden’s profound commitment to Trumpeter Swan conservation demonstrates one point most clearly – one individual can make a difference.

Young swans remain with their parents during the first winter. First-year swans are easily recognized by their darker colouration, most noticeable on the head and neck

Hastings County has its own local heroes. Bob and Lynn Gapes of Marmora started to feed a handful of over-wintering swans in 2005. Bob passed away in 2010 but Lynn continues her morning ritual of feeding swans to this very day. Between 30 and 40 swans greet Lynn almost every winter morning for handouts of corn. Historical migratory traditions of Ontario’s Trumpeters were lost when the swans were wiped out in the 1800s. Now, swans over-wintering in Ontario rely on artificial feeding to supplement their natural diets. Re-establishing migratory routes to milder winter ranges in the United States remains one of the challenges facing conservationists.

The hours that I devoted to photographing swans this past winter were filled with wondrous moments. Captivated by the sights and sounds of a Trumpeter’s world, my thoughts of the turmoil and troubles in our human world quickly vanished. Often, the swans returned my scrutiny and watched me intently with their jet-black eyes, seeming to assess whether or not my tripod and telephoto lens represented a threat. Digital photography provides an amazing opportunity to share the exquisite beauty of swans and other birds. Viewing photographs is a distant second, however, when compared to a close personal experience on nature’s terms.

The skies above Hastings County once again echo the trumpeting calls of this spectacular bird. On a few spring days during the past five years, Trumpeter pairs have flown directly over my neighbourhood along the Crowe River. It is their loud resonating calls that first announce their presence and attract my attention. I always look up with wonder and awe, and contemplate what might have been – how very close we came to losing for all time this majestic swan.

.jpg)

].jpg)

.jpg)

.png)